How Did Monterey Get to Become Monterey?

Jim Weed

Volume 49 Issue 16

Aug 24, 2024

In honor of Monterey Car Week, this article was first printed in August 2013.

I bring it back eleven years later to highlight the history of the region and why we return to this area like lemmings to the sea.

In honor of Monterey Car Week, this article was first printed in August 2013.

I bring it back eleven years later to highlight the history of the region and why we return to this area like lemmings to the sea.

Monterey. The word alone conjures up in one’s mind beautiful rolling hills, a picturesque harbor inlet, the sea crashing on the rocky seaward shore, and automobiles. Wait, automobiles? How could we get that vision of automobiles?

The history of the area has been connected with cars for more than a century.

By 1892 a scenic road called the 17-Mile Drive meandered along the beaches and forested areas between Monterey and Carmel. The Hotel del Monte was the starting and finishing point of a pleasure excursion intended to attract wealthy buyers of large and scenic residential plots.

Scenic attractions along the route include Cypress Point, Bird Rock, Point Joe, Pescadero Point, Fanshell Beach and Seal Point. The famous Lone Cypress was the midway point along the original drive. Sightseers riding horses or carriages would often stop at Pebble Beach to pick up agate and other stones polished smooth by the waves.

In its prime, Hotel del Monte was a 20,000-acre resort complex with extensive botanical gardens and sports facilities with polo grounds and a race track, albeit for horses. Golf started in America in 1894, and it didn’t take long before the first golf course was carved out on the Del Monte property. The oldest continuously operating golf course west of the Mississippi started with nine holes in 1897 and added another nine holes in 1899.

Del Monte hotel, circa 1885

By 1915, Hotel del Monte and its parent corporation, the Pacific Improvement Co., had fallen on hard economic times. The company hired 30-year-old Samuel F. Morse to serve as liquidator and find buyers for several railroad properties, including the Del Monte. He initiated several innovative programs including the development of the Pebble Beach golf course. Morse formed Del Monte Properties Co. in 1919 to purchase the Hotel del Monte, Del Monte Lodge and the 20,000-acre resort complex.

The Del Monte Properties Co. imagined the area as a “sports empire” and built more golf courses, including Cypress Point and Monterey Peninsula Country Club to go along with the polo fields, tennis courts, swimming, yachting, deep sea fishing, horseback riding, and horse racing track.

The wealthy and famous came to enjoy the resort, the many relaxing activities, to be sheltered from the everyday pressures, and a place to unwind and be seen. The Del Monte offered the finest cuisine, and created an indelible legacy of art, architecture and environment that helped to preserve the region’s dynamic history and culture even as it redefined the Monterey Peninsula.

With the call-up of men for World War II, many of the armed services requisitioned existing buildings and hotels to provide training and schools. Hotel Del Monte was closed and leased to the Navy for electronic technician training.

Throughout the war, the best station assignment was Monterey. After the end of hostilities, the Navy purchased the hotel and surrounding 627 acres in 1947. The Navy today continues to occupy the hotel, now called Herrmann Hall, as the central building of the Naval Postgraduate School.

Here is when automobiles enter the picture. Del Monte Properties Co. President Jack Morse, son of Pebble Beach founder Sam Morse, had gone to Yale with Sam and Miles Collier. The brothers had founded the Automobile Racing Club of America in 1933. This was the forerunner of the modern Sports Car Club of America (SCCA) formed in 1944.

Another close friend was Sterling Edwards who was a member of the San Francisco Region SCCA and a racer. Edwards convinced Morse to provide a venue for a race. Morse was fully aware of the positive effect of sporting events on the attendance of the company’s Pebble Beach Lodge and had previously sponsored golf, tennis, and other tournaments.

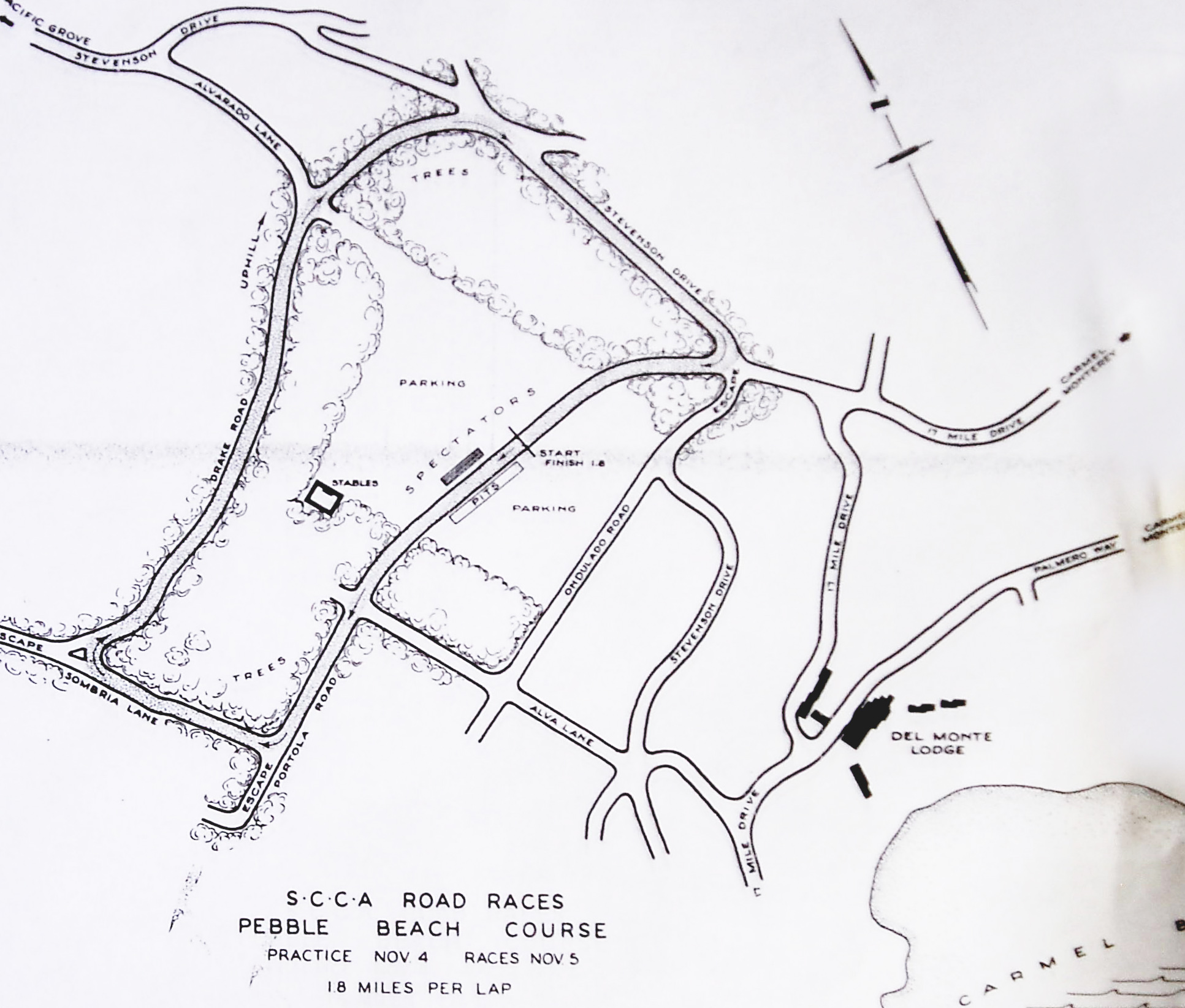

The “Del Monte Trophy” was held in November 1950 on the twisty, leafy, and narrow town roads. This first race ended with a now famously inspired drive by Phil Hill in a highly modified Jaguar XK-120. Not all the track was paved. The original route consisted of both paved two-lane roads and sections of dirt or loose gravel.

The circuit was exceedingly dangerous. Spectators stood or sat right at its edges, and trees lined the course. Although the course was always tight and twisty, accidents were scarce and relatively uneventful. The Pebble Beach road course was used in various configurations until 1956.

The course was recognizably dangerous as crowds grew and the cars became faster. The end of racing on the streets came when Ernie McAfee was killed driving a Ferrari 121 LM (S/N 0546 LM) into a tree. Fortunately, no spectators were hurt, but the speeds dictated a change in venue.

Sterling Edwards in 1954

To complement the weekend race, Del Monte Properties added the concours also in 1950. A separate committee was set up to organize the event. The site was a practice tee and driving range on the golf course next to the Del Monte Lodge. A total of 31 automobiles showed up, three of which were cars entered in the next day’s race.

Alton Walker, a local resident and car collector, brought four of his Brass Era cars. Other entries included a Type 57 Bugatti, a Darrin Packard, a LeBaron-bodied Chrysler and others more recently delivered from showrooms. It was these ‘new’ cars that took the trophy the first four years.

The mold was broken in 1955 when Phil Hill brought the family 1931 Pierce-Arrow 41 Town Cabriolet by LeBaron and was awarded Best of Show. This win was the turning point for the concours; the future was cemented in celebrating the classic automobile.

Phil Hill winner of the 1955 Pebble Beach Concours

Let’s go back to the required change in the racing venue. Fort Ord was established in 1917 as a maneuver area and field artillery range. Originally named Gigling Reservation, it became Fort Ord in 1940. The base commander in the early days of World War II was the famous ‘Vinegar Joe’, Joseph Stillwell. This was the home of the 7th Infantry Division and with the expansion of the base it was said a building was completed every 54 minutes.

Troops assigned to the area later in the war were trained in amphibious operations using the fine beaches along the coast. It would be on some of this land one of the most challenging and interesting race tracks would be constructed.

Gen. Curtis LeMay, commander of Strategic Air Command, loaned out air bases for the SCCA’s use. General LeMay was a sports car enthusiast and owned an Allard J2. It was his efforts that helped the military see the value in providing a venue for racing. Sports Car Racing Association of the Monterey Peninsula (SCRAMP) organized and began to negotiate with the Army to lease a tract at a site called Laguna Seca to build a race track.

SCRAMP negotiated a five-year deal and $3,000 to the Army for the use of the land. Construction started during the first week of September 1957 and the track was finished 60 days later for the first race held November 9 and 10. When Major Gen. Gilman C. Mudgett cut the ribbon on Laguna Seca, more than 35,000 spectators and 100 entries showed up.

Since the distance had grown between the races and the concours, what was once an afterthought had to come into its own. The Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance shifted from the spring to the autumn and back. It continued to be paired with races but now was looking to find its place in automotive history.

During the rest of the 1950s and even into the 1960s, the Pebble Beach Concours soldiered on. It was a concours with many fine cars coming from all around the country, but the ‘elegance’ part was missing. The weekend show was becoming a show, not an event. The cars promised to show would not; the crowds, although steady, were declining. The Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance was not what is should or could be.

The 1972 concours experienced a total overhaul by two former judges, Lorin Tryon and Jules Heumann. These gentlemen put the Elegance back into the Concours. The automobile classes were overhauled. Judging became a serious affair with experts in various marques tapped for their knowledge. With unfailing effort and time, Lorin tracked special and unique restorations. Jules saw to the organization. The die had been cast.

Steve Earle had old racing cars and a dream. “There needed to be an event we could come to and run the cars,” he once said. “We needed to share the cars with people who had an interest in old races and cars.”

So, Earle rented Laguna Seca Raceway, called everybody he knew and coordinated with the Pebble Beach Concours. The First Monterey Historic Automobile Races were held in 1974. The races would build on the early history of racing in Pebble Beach and complement the weekend. Racing was on Saturday with the concours on Sunday.

250 LM, Laguna Seca 1989

From these changes and refinement of the formula started 20 odd years earlier, the Monterey classic car weekend began to grow. Each year more spectators would arrive for the racing, and more cars would submit to run the historic track.

The concours crowds became larger and a new respect for the quality of restorations, the saving of significant automobiles, the desire to share rare and obscure cars with the public, cemented the weekend in August as the automotive Mecca.

The final piece of this grand experience started in the mid-1990s with the addition of a Christie’s auction. It was now possible to visit Monterey, enjoy exciting vintage racers at speed around the track, dress up for an elegant concours and visit an auction to purchase your own piece of history so that it would be possible to return next year, not as a spectator, but as a participant.

This draw was so great that within the next seven years there were no less than six auction houses holding their sales in and around the Monterey area. Each year the auctions sell many millions of dollars in automobiles. In addition, many of the automobiles are significant in rarity or history, and many times both. Record prices seem to be had each year as each auction house attempts to outdo the next.

The event has become so large and varied it now lasts an entire week. Between auctions, racing, road rallies and the concours it has become difficult, nay, impossible, to take it all in. But that should be no reason to not be there. Go once, and you’ll be hooked. Go twice, and you’ll be hooked for life. There are beautiful rolling hills, a picturesque harbor inlet, the sea crashing on the rocky seaward shore, your new friends, and of course the automobiles.

The history of the area goes back much further.

In June 1542, Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo, a Portuguese sailor, journeyed up the west coast of North America on behalf of Spain. He was the first European explorer to navigate the uncharted west coast of these new lands.

Cabrillo set out with three ships from Navidad in Jalisco, which was in New Spain (Mexico). In September he landed in what is now San Diego Bay; a week later he reached Santa Catalina Island. His path then followed to San Pedro Bay, then up to Santa Monica Bay and further to Point Conception at the Santa Barbara channel.

By November, Cabrillo had sighted Point Reyes but missed the entrance to San Francisco Bay; this would be a lapse mariners would repeat for the next 200. The expedition traveled further north about 60 miles to the mouth of the Russian River before the autumn storms forced him to turn back. It was on the return trip that Cabrillo entered Monterey Bay.

In 1601, the Spanish Viceroy in Mexico City, Gaspar de Zuniga Acevedo y Fonseca, (the Fifth Count of Monterrey), appointed Sebastian Vizcaino general-in-charge of an expedition to locate safe harbors in upper California for Spanish galleons to use on their return voyage from Manila to Acapulco.

Vizcaino was also given the mandate to map, in detail, the California coastline that Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo had reconnoitered 60 years earlier. Vizcaino departed May 5, 1602, with three ships and from that voyage he explored San Diego Bay and named Catalina Island. On Dec. 16, Vizcaino anchored in what is now the Monterey Harbor and named it Puerto de Monterey in honor of Fonseca.

Vizcaino was also the first person in recorded history to note certain ecological features of the California coast such as the Monterey Cypress Forest at Point Lobos. One result of Vizcaino’s voyage was a flurry of enthusiasm for establishing a Spanish settlement at Monterey, but this was deferred for 167 years.

The Lone Cypress at Pebble Beach

The port of Monterey which had been visited and charted a century and a half before was ripe for colonization and military fortification. In 1768, General José de Gálvez, the Viceroy of New Spain, received the following orders: “Occupy and fortify San Diego and Monterey for God and the King of Spain.” Two years later, a small expedition led by Captain Gaspar de Portolá and Father Junípero Serra officially took possession of the Alta (upper) California Province, what is now central California, via the establishment of El Presidio Real de San Carlos de Monterey (the Royal Presidio of Saint Charles of Monterey) and the nearby Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo.

Father Serra relocated to the Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo and remained there as “Father Presidente” of the Alta California missions and it served as his headquarters. When he died on Aug. 28, 1784, he was interred beneath the chapel floor.

Monterey became one of a series of presidios, or “royal forts,” built by Spain. The founding of the city of Monterey in 1777 marked the beginning of settlement in upper Las Californias in New Spain. Monterey served as the capital of upper Las Californias and Alta California from 1777 to 1848, under the flags of Spain, independent Mexico, and as a territory, the United States.

The city was originally the only port of entry for taxable goods in California. All shipments into California by sea were required to go through the Custom House, the oldest governmental building in the state, and California’s Historic Landmark No. 1.

Built in three phases, construction on the Custom House began in 1814 under the Spanish. The center section was constructed under Mexican rule in 1827, with the lower end completed by the United States in 1846.

Hostilities between U.S. and Mexican forces had been underway in Texas since April 1846, resulting in a formal declaration of war on May 13, 1846, by the U.S. Congress between Mexico and the United States.

Commodore John D. Sloat, commander of the U.S. Navy’s Pacific squadron, dispatched his flagship to Monterey harbor. There were U.S. fears that the British might try to annex California to satisfy British creditors. Sloat instructed the captains of his ships to occupy Monterey with their Marines and Navy sailors.

The California soldiers had already left the town’s defenses and gone to Los Angeles. More than 220 U.S. Navy officers, sailors and Marines landed unopposed and captured Monterey without incident. On July 7, 1846, Sloat raised the U.S. flag over the Monterey Custom House and claimed California for the United States.

Many California “firsts” have occurred in Monterey. These include California’s first brick house, theater, publicly funded school, public building, public library and printing press, which printed The Californian, the first newspaper. Colton Hall, built in 1849, was originally a public school and government meeting place. The Monterey post office also opened in 1849.

Approximately 36 miles northeast, gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill. The gold rush of 1849 brought masses of people to California. San Francisco, founded in the 1770s, began to boom. The bay and docks were better equipped to handle the massive influx of people with gold fever.

Monterey, the seat of government in the new territory, held California’s first constitutional convention in September 1849. One year later California was admitted into the Union as the 31st state. Due to the protection of Sutter’s Fort, the city of Sacramento, established in 1839, became a major distribution point, commercial and agricultural center and a terminus for wagon trains. In 1854 Sacramento became the new capital. As California grew by leaps and bounds, Monterey seemed to be cast aside.

Whaling began in 1854 in Monterey Bay, and during the next 50 years the bay became host to several companies engaged in capturing and processing whales for the ever-increasing demand for whale oil.

So for Monterey, the thriving city and gateway to the interior, political and governmental power slowly declined into just another seaside sailor town filled with bars, billiards and more. By 1888 the whaling boom time was over, the price for whale oil declined as lower priced alternatives such as kerosene and petroleum oil came into the market.

The transition from Mexican lands and American Territory to the 31st state created many land title disputes. A gentleman named David Jack had been elected treasurer of Monterey County in 1852 and began to involve himself in the settlement of Mexican land claims in the new state of California.

This process would lead Jack to become Monterey’s dominant landowner. In 1869 Jack acquired sole interest in a tract that included what are now the cities of Monterey, Pacific Grove, Seaside, Fort Ord and Del Ray Oaks along with the Del Monte Forest.

Jack owned a dairy along the Salinas River and produced a cheese originally known as Queso Blanco, first made by the Franciscan padres at the nearby Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmello. As Jack’s dairy went into partnership with other regional dairies, the cheese was marketed as “Jack’s Cheese” and eventually “Monterey Jack.”

During the 1860s the Civil War raged in the east, and the federal government wanted to keep California on the Union side. A transcontinental railroad was proposed, and work commenced. Railroading created much wealth and one gentleman, Charles Crocker, made a fortune with the Southern Pacific Railroad.

Crocker recognized the natural beauty of the Monterey Bay and Carmel Valley area. Southern Pacific Railroad’s property division, the Pacific Improvement Co., purchased a large tract of land between Carmel and Pacific Grove from David Jack.

The Hotel Del Monte opened in June of 1880, and it was the first true resort complex in the United States. It offered hunting and other outdoor activities. The Del Monte was instantly popular, and the hotel had to turn down requests for accommodation within the first six weeks of operation. Often billed as “The Most Elegant Seaside Resort in the World,” the hotel became popular with the wealthy and influential of the day.